Author:

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD

Article Type:

Feature Article

The word

hygiene comes from

Hygeia, the Greek goddess of health (photo, below), who was the daughter of Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Since the advent of the Industrial Revolution (c.1750-1850) and the discovery of the germ theory of disease in the second half of the nineteenth century,

hygiene and sanitation have been at the forefront of the struggle against illness and disease.(1)

Together with the great strides made in improvements in the standards of living provided by free market capitalism, economic freedom, and the advances in scientific medicine --- hygiene and sanitation have resulted in unprecedented longevity, concomitant with markedly improved quality of life in the last century and a half of medical history.

Thanks to these advances, senior citizens, particularly octogenarians, have become the fastest growing segment of our population even though the priority assigned to the prolongation of life span has taken a back seat to other items in health care policy, chiefly the containment of health care costs and "the proper allocation of finite and scarce health resources." Thus, the concept of longevity (from the Latin longaevitas, meaning "long-lived") has been almost abandoned for the new, modern concerns of "useful life span," "the duty to die," "assisted suicide," and so on.

Nevertheless the dramatic extension of life span closely associated with improvement in the quality of life is welcomed news for the American "baby boomers," who have the most to gain from advances in longevity as they age in the first half of the twenty-first century.

In the Middle Ages, the average human life expectancy did not reach into the teen years, not only because of the extremely high perinatal mortality that heavily skewed the data, but also because Europeans (and much of the world during this time) lived in an unhealthy milieu of filth, poor hygiene, and nearly non-existent sanitation. Superstition and ignorance, along with pestilential diseases and vermin infestation, were rampant. Epidemic and endemic diseases such as the bubonic plague, typhus, variola (smallpox), and the White Death of tuberculosis (consumption) took a heavy toll on the population, both young and old.

During the Middle Ages until the mid-nineteenth century cleanliness was just not a priority. The streets in those days were dumping grounds for refuse, and domestic animals including hogs roamed the streets. According to medical historian Howard W. Haggard: "Refuse from the table was thrown on the floor to be eaten by the dog and cat or to rot among the rushes and draw swarms of flies from the stable. The smell of the open cesspool in the rear of the house would have spoiled your appetite, even if the sight of the dining room had not."(2)

There was little improvement in this dire, unhealthy milieu until the mid- to late nineteenth century when the advances of the aforementioned Industrial Revolution and the discovery of the germ theory of disease brought about public health measures that, building upon the importance of good hygiene and sanitation, culminated in the rise of the scientific era of medicine. The heroes and heroines of this age included such notable medical figures as: Edward Jenner (1749-1823), Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), Ignaz Semmelweiss (1818-1865; photo, right below), Florence Nightingale (1820-1910; photo, left below), Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902), Clara Barton (1821-1912), Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), Joseph Lister (1827-1912), J. Henri Dunant (1828-1910), and Robert Koch (1843-1910).

In the words of the surgeons and medical writers Nathan Hiatt and Jonathan R. Hiatt, "The industrial revolution, however, also brought a raised standard of living, with higher wages,

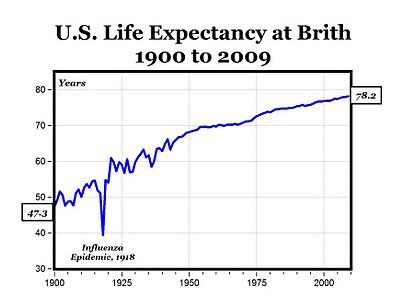

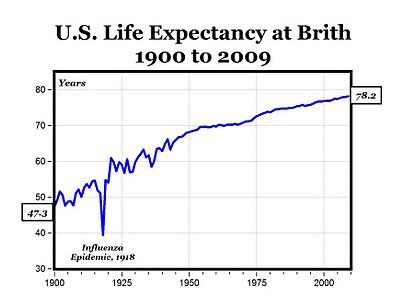

improved nutrition, cheap soap, and inexpensive cotton clothing. Cotton clothing, unlike the louse-ridden woolens worn in the past, could be and had to be washed, thus dispossessing lice and helping to end typhus epidemics. By 1900, improved nutrition, better sanitation, and, especially, contributions from bacteriologists increased life expectancy at birth by almost six years (to age 47.3)..."(3)

Of particular importance in medical history, puerperal fever was one of those diseases that intrigued and baffled doctors in the nineteenth century. You might even remember the famous painting of the illustrious Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes delivering his famed lecture on the subject to the Boston Medical Society in 1843. Just as Dr. Semmelweiss had predicted, the disease was conquered when obstetricians began washing their hands between deliveries. Puerperal fever was eradicated with cleanliness. Likewise, surgical mortality became acceptable when surgeons began washing their hands and using antiseptic techniques as urged by Dr. Joseph Lister. The scientific tenets of bacteriology and microbiology introduced by Louis Pasteur were finally being applied to obstetrics, medicine and surgery.

The engine behind the drive for hospital reform in the mid-nineteenth century was Florence Nightingale (photo, left). After her tremendously successful humanitarian venture at the Scutari Barrack Hospital during the Crimean War, Nightingale was able to convince the world of the necessity of improving hygiene and sanitation as well as having trained professional nurses tending the sick in the hospital wards. According to medical historian Guy Williams, when she arrived at Scutari "there were plenty of rats, lice and fleas, but there were very few knives, forks, or spoons. Miss Nightingale and her nurses, who were allowed just one pint of water per person per day for washing and drinking and for making tea, [yet]...the ladies' own personal circumstances were hardly hygienic."(4) With hard work and determination, she turned the situation around and by the time she returned to England, she had become a national heroine.

Maternal mortality, a dreaded and common complication of pregnancy throughout the ages, was all but conquered in the West in the twentieth century by a three-pronged attack of public health, particularly the efforts at better hygiene and sanitation; improved obstetrical care, and the use of antibiotics.

The period between 1930 and 1940 saw a sharply rising curve in longevity rates thanks to the widespread usage of antibiotics and the much improved standards in cleanliness, hygiene, and sanitation. Thereafter, further reductions in maternal and infant mortalities were to a significant degree responsible for the tremendous rise in life expectancy. With the conquest of such diseases and scourges of humanity as syphilis, pneumonia, diphtheria, typhoid fever, typhus

, and earlier in the century, the old consumptive killer, tuberculosis --- life expectancy climbed from 59.7 years in 1930 to 74.9 years by 1987.

By the 1980s, the widespread availability and use of sulfa drugs and penicillin atop earlier traditional public health measures prolonged life beyond all expectations. These traditional health measures included: isolation of the sick during epidemics; quarantining of ships at ports of disembarkation; disinfection of fomites; exposure to fresh air and the beneficial rays of sunlight; and widespread immunization practices. The impact of these measures was enhanced by education and promotion of personal hygiene and communal sanitation, including the use of potable, running water and the proper disposal of wastes.

With the avoidance of self-destructive behavior, cessation of smoking, maintenance of ideal body weight, proper regime of exercises, adequate control of blood pressure and cholesterol levels, proper management of stress, and so on, one can still stretch his or her life span considerably in the twenty-first century.

Consider that over 80 percent of diseases are associated with unhealthy lifestyles and self-destructive behaviors and thus are subject to healthy alterations in behavior.(5) Needless to say, as the author has pointed out elsewhere, the possibilities for improvement become enormous. Maximal life span, redolent of the search for the fountain of youth by Ponce de León, has been estimated to be 114 years. Thus, there is still room for improvement!(1)

Protecting our health can even reduce health care costs and save money in the process. The money saved can then be spent when we reach a ripe old, antediluvian age, when most of us have reached our personal best in terms of knowledge and wisdom!

References

1. Faria MA Jr. In search of the fountain of youth. Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine. Macon, GA: Hacienda Publishing, Inc., pp. 121-125.

2. Haggard HW. The Doctor in History. New York, NY: Dorset Press, 1989.

3. Hiatt N, Hiatt JR. A history of life expectancy in two developed countries. The Pharos 1992;(55)2:3.

4. Williams G. The Age of Miracles - Medicine and Surgery in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago, IL: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1981.

5. Faria MA Jr. Vandals at the Gates of Medicine - Historic Perspectives on the Battle Over Health Care Reform. Macon, GA: Hacienda Publishing, Inc.

http://www.haciendapub.com.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Editor emeritus of the Medical Sentinel of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS), http://www.haciendapub.com. This article on the history of medicine is excerpted in part from Dr. Faria's Vandals at the Gates of Medicine

(1995) and Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine

(1997). Copyright©2002 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD.

Originally published in the Medical Sentinel 2002;7(4):122-123. The photographs used to illustrate this article came from a variety of sources and did not appear in the original Medical Sentinel article. They were added here for the enjoyment of our readers.

Copyright ©2002 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

hygiene and sanitation have been at the forefront of the struggle against illness and disease.(1)

hygiene and sanitation have been at the forefront of the struggle against illness and disease.(1) During the Middle Ages until the mid-nineteenth century cleanliness was just not a priority. The streets in those days were dumping grounds for refuse, and domestic animals including hogs roamed the streets. According to medical historian Howard W. Haggard: "Refuse from the table was thrown on the floor to be eaten by the dog and cat or to rot among the rushes and draw swarms of flies from the stable. The smell of the open cesspool in the rear of the house would have spoiled your appetite, even if the sight of the dining room had not."(2)

During the Middle Ages until the mid-nineteenth century cleanliness was just not a priority. The streets in those days were dumping grounds for refuse, and domestic animals including hogs roamed the streets. According to medical historian Howard W. Haggard: "Refuse from the table was thrown on the floor to be eaten by the dog and cat or to rot among the rushes and draw swarms of flies from the stable. The smell of the open cesspool in the rear of the house would have spoiled your appetite, even if the sight of the dining room had not."(2) improved nutrition, cheap soap, and inexpensive cotton clothing. Cotton clothing, unlike the louse-ridden woolens worn in the past, could be and had to be washed, thus dispossessing lice and helping to end typhus epidemics. By 1900, improved nutrition, better sanitation, and, especially, contributions from bacteriologists increased life expectancy at birth by almost six years (to age 47.3)..."(3)

improved nutrition, cheap soap, and inexpensive cotton clothing. Cotton clothing, unlike the louse-ridden woolens worn in the past, could be and had to be washed, thus dispossessing lice and helping to end typhus epidemics. By 1900, improved nutrition, better sanitation, and, especially, contributions from bacteriologists increased life expectancy at birth by almost six years (to age 47.3)..."(3) The engine behind the drive for hospital reform in the mid-nineteenth century was Florence Nightingale (photo, left). After her tremendously successful humanitarian venture at the Scutari Barrack Hospital during the Crimean War, Nightingale was able to convince the world of the necessity of improving hygiene and sanitation as well as having trained professional nurses tending the sick in the hospital wards. According to medical historian Guy Williams, when she arrived at Scutari "there were plenty of rats, lice and fleas, but there were very few knives, forks, or spoons. Miss Nightingale and her nurses, who were allowed just one pint of water per person per day for washing and drinking and for making tea, [yet]...the ladies' own personal circumstances were hardly hygienic."(4) With hard work and determination, she turned the situation around and by the time she returned to England, she had become a national heroine.

The engine behind the drive for hospital reform in the mid-nineteenth century was Florence Nightingale (photo, left). After her tremendously successful humanitarian venture at the Scutari Barrack Hospital during the Crimean War, Nightingale was able to convince the world of the necessity of improving hygiene and sanitation as well as having trained professional nurses tending the sick in the hospital wards. According to medical historian Guy Williams, when she arrived at Scutari "there were plenty of rats, lice and fleas, but there were very few knives, forks, or spoons. Miss Nightingale and her nurses, who were allowed just one pint of water per person per day for washing and drinking and for making tea, [yet]...the ladies' own personal circumstances were hardly hygienic."(4) With hard work and determination, she turned the situation around and by the time she returned to England, she had become a national heroine. , and earlier in the century, the old consumptive killer, tuberculosis --- life expectancy climbed from 59.7 years in 1930 to 74.9 years by 1987.

, and earlier in the century, the old consumptive killer, tuberculosis --- life expectancy climbed from 59.7 years in 1930 to 74.9 years by 1987.